by Barbara Solomon Josselsohn from

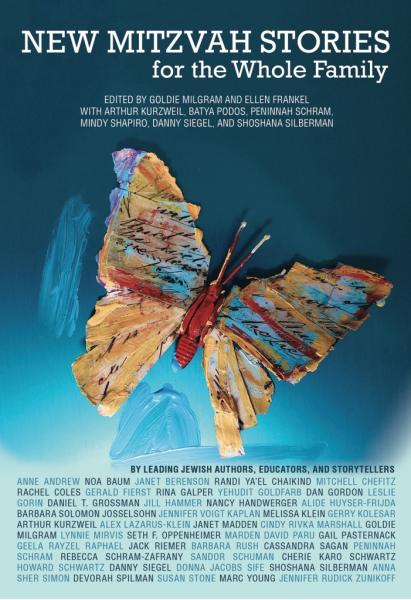

New Mitzvah Stories for the Whole Family

Most times a stranger is a person you don’t know. But sometimes a stranger is someone you thought you knew very well.

That was the case with my Aunt Maria, who I thought was the meanest, most prejudiced person in the world. I thought she hated Jews, which is weird since she’s married to my Uncle Dan, who’s my mother’s brother and definitely Jewish. I guess she decided to ignore that about him when she fell in love with him. But the rest of us were a different story.

Aunt Maria and Uncle Dan came to our house every year for Passover Seder, and Aunt Maria always made it clear from the moment she stepped inside that she didn’t want to be there at all. She’d pursed her thin lips and looked down her pointy nose at us as my dad passed out the Haggadot, and she never once smiled or nodded when Uncle Dan began chanting Hebrew—and he’s the best Hebrew chanter I ever heard. She’d constantly looked ahead in the book to see how many pages were left, and she’d sigh impatiently when she saw there were still a lot. She didn’t know any of the verses of Dayenu, and barely opened her mouth to sing when Uncle Dan poked her with his elbow to join in the chorus—and how could somebody pretend not to be able to sing the chorus of Dayenu? It was only that one word—Dayenu!

And she was always insulting the food. Like last year, when my mom handed her the platter of gefilte fish, she firmly said, “No, thanks,” baring her lower teeth and leaning away from the table, as though she couldn’t stand to be near the little gray logs one moment longer.

“I’m with you, yuck!” said my little brother Jake, as he transferred the platter from Aunt Maria to my father. My mother immediately asked to speak to Jake alone in the kitchen. But no one said anything to Aunt Maria.

The only time Aunt Maria looked happy at Passover was when the Seder was over and the meal started, because then she would talk about Easter. She’d tell us that her two teenage sons, who were out with friends and not at our dinner, had already outgrown their old suits and bought news ones for Easter Sunday. She’d tell us how much she loved the Easter service at her church.

“Oh, the lilies and tulips are spectacular,” she’d say. “And the music is so beautiful, it makes you tremble.”

“It sounds lovely, Maria,” my mother always said, ignoring that she’d taught us years ago you’re not supposed to visit one place and spend the whole time talking about how you’d rather be somewhere else. My mom is a teacher, and she’s big on consequences, so if Jake or I had talked about how much we’d like to be at a friend’s house or a movie, we’d get no dessert for sure. But Aunt Maria—my mom all but rewarded her for gushing over Easter while sitting at our table.

Plus, as if talking about Easter weren’t bad enough, each year sometime after Passover, Aunt Maria would have us over to her house on Long Island for a big Easter celebration. She invited lots of people from her side of the family—baby nieces and nephews, old aunts and uncles, and cousins of all ages. The highlight was a backyard Easter hunt, when all the kids would search for chocolate eggs wrapped in colorful foil, and little yellow marshmallow chicks in clear plastic wrappers. I wished so badly that I could turn down my mouth at the mention of Easter chocolates, or say a firm “No, thank you!” when the decorated baskets for collecting candy were passed around. But I couldn’t. The candy was too delicious and the hunt too much fun, and before I knew it, I was racing among the bushes and calling out, “Found one!” just like all the other kids.

The year I turned eleven, I decided—once and for all—to reject the Easter festivities. I didn’t have to be so obvious about it that my mom would notice and get mad. I could simply stand around and maybe yawn a few times if Aunt Maria happened to look over. Why not? After all, Aunt Maria was always nasty about our holiday. Why did we have to be polite about hers? What was fair about that?

But as the time of the hunt approached, I worried: Would I be able resist? Could I really just watch Jake and the others gather all the treats, and not be tempted by all the candies waiting to be plucked from the tree branches or pulled out of the grass? Figuring my best weapon was distance, I slowly backed into the house when I saw the kids assemble at the starting line. My luck, Aunt Maria was coming downstairs at that very moment, carrying the baskets to hand out.

“Why are you inside, Michelle?” she asked. “The hunt is about to start.”

I wanted to tell her I wasn’t interested in her Easter silliness, that I much preferred our more mature and serious Passover customs, but I could hear my mom in my head warning me not to be rude. So I said the only thing I could think of. “I need to use the bathroom.”

“The one down here is occupied,” she said. “Go upstairs and use the one next to my bedroom. And hurry or you’ll miss everything.”

I found Aunt Maria and Uncle Dan’s bathroom, but since I didn’t really have to go, I washed my hands instead, lathering up twice just to waste some time. Then I went back into their bedroom. I could see through the window that the hunt had begun, with big and little kids happily circling bushes and digging near tree trunks. Their baskets looked about half full, which I knew from experience meant there were about ten minutes more to go. I wandered to Aunt Maria’s dresser, which was crowded with photos of weddings and other family events. I ran my finger over the frames, trying to guess how long ago each was taken.

Then I noticed a small black-and-white picture in the corner.

It wasn’t framed, just lying flat on wood surface. I picked it up. Although the image looked old and faded, I could see a pretty young woman with shoulder-length wavy hair, and a small girl with dark bangs cut straight across her forehead. Long ago, it seemed, someone had written two names along the bottom border of the picture: Rivka and Chana.

Now even though my mom taught Hebrew, I wasn’t exactly the best student at our temple. Still, I did know that Rivka and Chana were Jewish names, which made me totally confused. If Aunt Maria hated Jewish things so much, why did she have an old picture of a Jewish lady and a girl on her dresser, next to all her important family photos? Who were these people and why did they belong here?

I was so curious that I slipped the photo into my jacket pocket, thinking I could ask my mom about it and return it to the dresser without Aunt Maria knowing. But when I got downstairs, I was suddenly hungry, and jealous of all the kids munching on chocolate eggs and sticky marshmallows. Running over to see if I could persuade Jake to share some of his stash, I forgot all about the photo until two afternoons later, when I was getting ready to do homework and dug into my jacket pocket, looking for my favorite mechanical pencil.

My shoulders fell, as I thought about how much trouble I was going to be in for taking the picture from Aunt Maria’s bedroom. But since I couldn’t wait all the way until next Easter to put it back, I decided to confess and get it over with.

My mom was sitting at the kitchen table, going over some of her students’ homework.

I put the photo on the table in front of her.

“Who are these people?” I asked.

She picked it up. “Rivka and Chana? That’s Aunt Maria’s mother and grandmother. Where did you get this?”

I couldn’t believe what she said. “You mean…Aunt Maria is Jewish?”

My mom took off her glasses. “You didn’t answer my question. Where did you get this?”

I looked down. “From Aunt Maria and Uncle Dan’s bedroom,” I said softly.

“From their bedroom? What on earth were you doing in their bedroom?”

“I had permission—really, Mom,” I told her. “Aunt Maria told me to go up there and use her bathroom. And I saw this on her dresser and wanted to ask you about it. But when I got downstairs and saw all the candy, I…sort of forgot that I put it in my pocket.”

My mom sighed. “Oh, Michelle, what were you thinking? You know not to take things from someone’s home without permission.”

“It was an accident,” I said. “I just meant to show it to you. But she’s so mean, she gets me all mixed up. And with the candy and everything, I wasn’t thinking straight.”

“You’re going to have to return it. And tell her what you did.”

“I know, and I’ll say how sorry I am. But really, Mom—how can she be Jewish? It doesn’t make sense. She hates Jews.”

“She doesn’t hate Jews.”

“She hates Passover. She hates Seders. She only loves Easter. She only loves Christian things.”

My mom motioned to me to sit down. “Michelle, do you know what the Holocaust was?

I nodded. “It was when the Nazis tried to get rid of all the Jews.”

“And do you know what the Kindertransport was?”

This time I shook my head no.

“It took place around that time, when many Jewish families weren’t able to leave Germany and other countries. So some parents sent their children off to England, so they’d be safe. Maria’s mother—that’s the little girl in the picture, Rivka—she was a Kindertransport child. Rivka’s mother, Chana, and her father were killed in the Holocaust.”

I suddenly felt so sad. I couldn’t imagine being sent away from home and never seeing my parents again.

“Rivka was raised in England by a family that wasn’t Jewish, and when she went to America, she married a man who wasn’t Jewish,” my mom said. “When Maria was born, they decided to raise her as a Christian. You see, Rivka associated Judaism with sadness and death. She didn’t want to pass that on to Maria.”

I felt my eyebrows press together. “But doesn’t Aunt Maria have to be Jewish? Because her mother was?”

My mom shook her head no. “You see, it’s clear for us—Daddy and I are Jewish, and you and Jake are Jewish, too. And we’re happy that way. But it’s not always that simple. Some people struggle to figure out how religion fits into their lives, or even if it does. And we need to respect their choices.”

“But Aunt Maria married Uncle Dan,” I said. “If she didn’t want to be Jewish so badly, why would she marry someone who was?”

She raised her shoulders to show she didn’t have an answer. “Maybe because she loved him so much. And maybe she was searching for a part of herself that was missing. Maybe she’s still searching now. Who knows?”

I rolled my eyes. “So that’s why we have to be nice to her when she’s mean to us on Passover?”

She reached out for my hand. “Michelle, do you remember the Torah story of Abraham and the three strangers?”

I shook my head no.

“Well, Abraham encountered three strangers one day, and he welcomed them into his home. He and his wife, Sarah, made them a good meal, and took care of all their needs. And as it turned out, these men weren’t just strangers. They were angels—messengers sent by God. And Abraham and Sarah were blessed for showing them so much kindness and hospitality.”

She put her hand under my chin. “I hope we’re like Abraham and Sarah to Maria. I like to think we’re a blessing to her. And even though things are sometimes strained, I think she’s a blessing to us, too.”

She stood up. “Now, go get your jacket, while I make sure Jake can stay next door until your dad gets home. You and I have an errand to do.”

An hour later, we arrived at Aunt Maria and Uncle Dan’s house. Aunt Maria was just getting out of her car, carrying two bags of groceries. I got out and walked up driveway.

“Aunt Maria?” I called.

“Michelle?” she said. “What are you doing here? Why’s your mom still in the car?”

I took the photo out of my pocket. “I took this picture from your house by mistake,” I said. “I saw it when I went up to your bathroom, and I was curious. I brought it down to show it to my mom, but then I forgot about it, and I just found it in my pocket today. I’m really sorry.”

My aunt put down the grocery bags and took the picture from me. “Thank you,” she said stiffly. “No harm done.”

I breathed in deeply. “And I’m really sorry about what happened to your family in the Holocaust,” I said.

She looked away, her eyes skyward.

“And I’m really sorry I didn’t participate in the Easter hunt this year,” I added. “It’s a really fun activity. It’s nice that you include my family.”

She looked at me. Her lips were a straight line. She was acting like she didn’t feel anything, but I think she was feeling a lot. “It’s nice for us to come for Passover too,” she said.

She slid the photo into one of the grocery bags and picked them both up, one in each hand. “Your mom is probably anxious to go. Thank you for coming by to return this.” She waved briefly at my mom and continued into her house. I watched her close the door firmly behind her, and then I went back to my car.

I wasn’t sure if Aunt Maria would still be a stranger to me the next Passover. I wasn’t sure how many more Passovers would come and go with her still a stranger. But I was sure of one thing. I was sure that I try really hard to always be kind and welcoming to Aunt Maria. And then, one day, maybe she would no longer be a stranger at all.

42 addional delightfully provocative stories by leading authors, storytellers and educators can be found in New Mitzvah Stories for the Whole Family (study guide included), Goldie Milgram and Ellen Frankel, Eds. with Arthur Kurzweil, Batya Podos, Peninnah Schram, Danny Siegel, Shoshana Silberman, and Mindy Shapiro

42 addional delightfully provocative stories by leading authors, storytellers and educators can be found in New Mitzvah Stories for the Whole Family (study guide included), Goldie Milgram and Ellen Frankel, Eds. with Arthur Kurzweil, Batya Podos, Peninnah Schram, Danny Siegel, Shoshana Silberman, and Mindy Shapiro

Bio for the author of "The Stranger at the Passover Table"

Barbara Solomon Josselsohn is a freelance writer whose articles appear in The New York Times, Consumers Digest, American Baby, Parents, Westchester Magazine, and other publications. She also teaches in the Religious School of Westchester Reform Temple in Scarsdale, N.Y., where she led a class of sixth-graders in writing a chapter book about a Torah that’s missing Noah—and the steps needed to get him to return! In addition, she conducts an annual children’s writing workshop at the JCC-MidWestchester, also in Scarsdale. She is currently working on a picture book about Rebecca and Isaac, and on her first middle-grade novel.